Location – On the summit of the Rock of Cashel.

OS: S 07479 40940

Longitude: -7.8905292

Latitude: 52.520083

Description and History – St. Patrick’s Cathedral, like Cormac’s Chapel, is a fantastic example of its style, but with its own unique idiosyncrasies. Built in the Gothic style, St. Patrick’s was not the first cathedral build at the Rock of Cashel. There was undoubtedly some form of church or cathedral constructed when the round tower was built in c1101. It was likely located at the east end of the site with the western door of this structure aligned with the door of the round tower, which was a common layout at the time. There may also have been a second cathedral constructed in 1169 and commissioned by Donal Mór O’Brien. No traces of this structure survive.

The present cathedral was begun around 1135, possibly at the hands of the archbishop Marianus O’Brien, although David MacKelly has also been suggested who also founded Dominic’s Friary in Cashel. The building was not, however, finished until the 1280s during the time of David McCarvill who served as archbishop between 1254 and 1289. The reason for this long construction period is unclear, but was likely due to financial issues. The Cathedral was, therefore, built in a series of phases beginning with the choir/chancel area, followed by the south transept and porch, and then the nave and north transept.

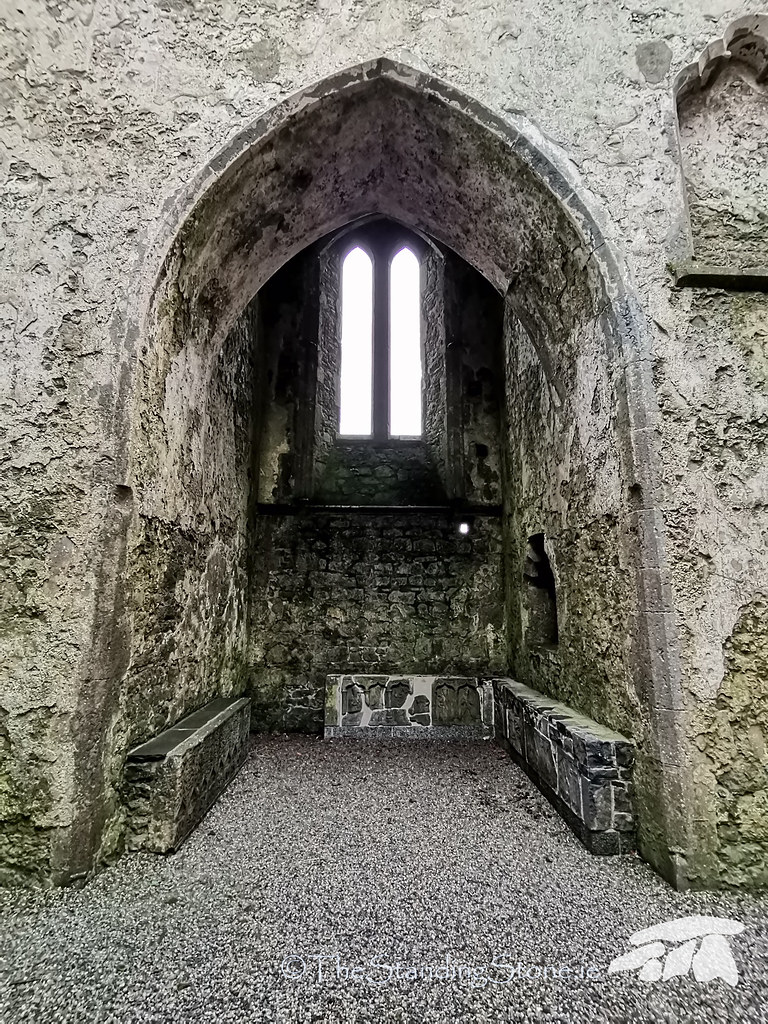

Architecturally St. Patrick’s Cathedral is built in the Gothic style which grew out of the Romanesque style in France and England in the late 12th century and was originally known as ‘French work’. Just as the Romanesque style was characterised by rounded archways, the Gothic style was characterised by its pointed archways which were better suited for supporting the weight of the walls above. Barrel vaults gave way to rib and groin vaults, and windows became larger and more elaborate in their use of tracery (the dividing up of a window opening into sections), which allowed for the introduction of stained glass. Gothic architecture sought height and light in contrast to the squatter and darker Romanesque style. At the Rock of Cashel this is plainly evident where the two styles sit side-by-side to each other in the form of Cormac’s Chapel and St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

St. Patrick’s Cathedral is cruciform in shape, and is divided into the nave (where the congregation would have sat), the choir and chancel (where mass would be said), and two transepts which contain several side chapels. Where all these sections meet is called the crossing. The crossing is formed by four elaborate 13th century pillars which rise to a plain ribbed vault. This vault was severely damaged during the attack in 1647 when the original bells were removed from the 15th century bell tower above. It was largely reconstructed in 1875.

There are two entrances into the Cathedral. The entrance on the south side has a porch with a well preserved groin vault. The corresponding porch on the north side no longer survives.

The nave is unusually short, the choir unusually long. Normally the nave is the longest part of a church or cathedral. It’s short length here may be due to the lack of building space at the Rock of the Cashel as the land slopes away sharply to the west. The nave may have also been shortened when the residential tower was constructed in the early 15th century. In the nave today there are two tomb niches. On the internal north wall is a tomb belonging to the Sall family who were important local merchants. The tomb dates to 1574, and shows a rare example of a merchant’s seal below the Sall coat of arms. On the south side is located a 17th tomb belonging to the O’Kearney family. It is decorated with ornate stucco plasterwork, showing a crucifixion scene, a coat of arms, and a centrepiece with four angels, the sun, moon and stars.

The choir, or chancel, is where the high altar was located. There was also an area for the choir to sing. Most of this area would have been screened off from the view of those in the nave as was custom at the time. Three tall lancet style windows would have lit the chancel on the East wall, but these have not survived. However, smaller lancet windows have survived on the south and north walls. In the chancel area, a piscina can still be seen. The piscina was a stone basin for the washing of sacred vessels. Next to this is a sedilia where celebrants sat at points during mass.

A series of grave slabs, not in their original location, are on the floor of the chancel, dating from the late 13th up until the 19th century. These are the grave slabs, clerics, merchants, and townspeople. Also located within the chancel are the wall tombs of two archbishops. The first is the elaborate tomb of the Archbishop Miler McGrath, mentioned earlier, and the second is of his successor Archbishop Malcolm Hamilton.

Each transept contains three large lancet style windows which were shortened in the 15th century. Passages run through the base of the pillars forming the windows and connect to spiral stairs which run to the top of the bell tower. There is an intricate series of passages and stairs which run throughout the Cathedral, hidden within the thickness of the walls. There are two side chapels in each transept which are now home to some well-preserved remains of 16th century tomb sculpture showing saints, angels, coats of arms, and a crucifixion panel.

Between the two side chapels in the south transept, is the remains of a large medieval wall painting depicting the crucifixion. St. Paul is depicted on Christ’s left holding a sword, while St. Peter is on Christ’s right holding the keys to the kingdom of heaven. Mary and John, smaller and almost completely lost, stand under the arms of the cross. While much of the painting is now lost to us, it was likely painted in the early 15th century, and gives us a small glimpse as to what the Cathedral was like at the time – a place full of art and colour.

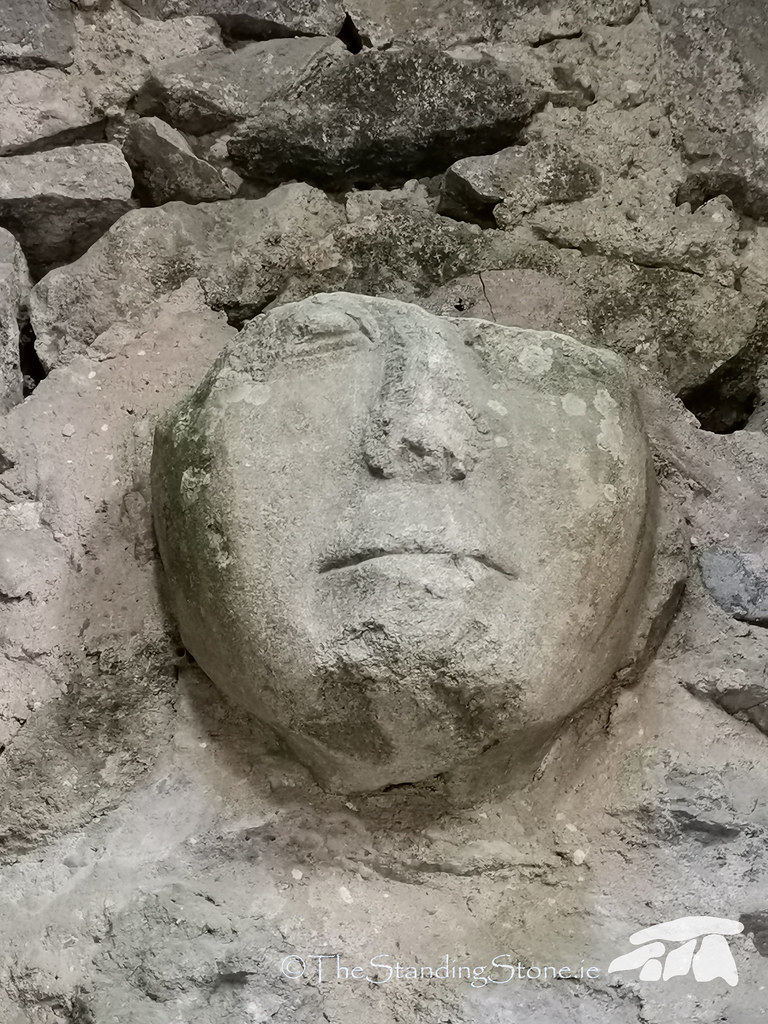

Throughout the Cathedral, both inside and out, are a series of carved heads. Both male and female, they show a range of facial expressions and could have been benefactors of the church or important local people.

Incorporated into the Cathedral is a rock cut stone well which is over 8m deep. It pre-dates the Cathedral and may be the only visible trace of the pre-ecclesiastical phase of the Rock of Cashel which began in 1101.

Difficulty – This is the largest building at the Rock of Cashel and is easy to navigate.